5. Cooperation and Conflict Studies in Chinese IR

(With Kai Wang and Xintong Chen)

Revise and Resubmit

Abstract: Although Western security scholarship often focuses disproportionally on conflict, cooperation-oriented research dominates Chinese security studies. To account for this divergence, we draw on Bourdieu’s notion of field as an analytic framework. We argue that a dual power asymmetry – the core-peripheral relations between Western and Chinese IR scholars, and the Chinese IR community’s structural dependence on the authoritarian party-state – profoundly shapes the knowledge production of Chinese security studies and leads to the hegemony of cooperation-centered research. We use a unique combination of empirical materials including bibliometric data from China’s leading IR journals, content analysis of projects funded by a prestigious Chinese government grant, and qualitative interviews with IR academics at Chinese institutions. We find strong evidence for our theoretical propositions. Our findings shed new light on the global IR debate, national IR parochialism, and the sociology of IR epistemic practice in non-democratic contexts.

4. Desperate Times Call for Desperate Measures: External Support, Internal Strength, and the Strategy of Minority Repression

(with Chen-Yu Lee and Howard Liu)

Under Review

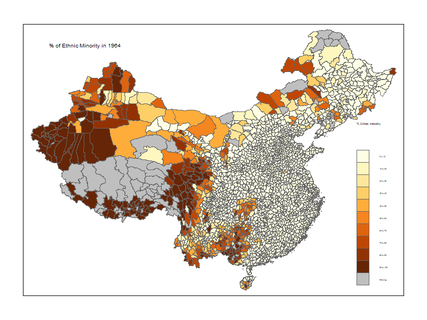

Abstract: Why do states, when facing ethnic separatist threats, sometimes opt for settler colonization while other times use extreme violence like genocide? Existing theories offer limited insights into variations in repressive choices. We propose that external support and a minority’s separation potential influence state choices. If external powers support a domestic minority group with weak insurgency capabilities, states favor a gradual approach, like internal colonization, to solidify control over minority-concentrated territories. However, when a minority group has strong insurgent capabilities and receives external support, the secession threat intensifies. This urgency pushes states towards immediate, drastic measures like genocide for swift control. Our research, using new data on ethnicity and violence from Mao’s China, corroborates this argument. The findings demonstrate how the immediacy of threats determines not only the presence but also the methods of repression and carry implications for human rights for minorities.

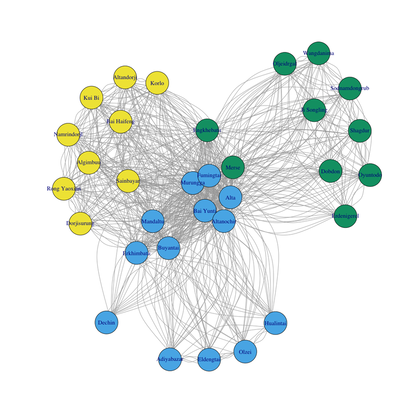

Abstract: Rebel groups are often susceptible to schism. In this paper, we depart from preexisting group-level analyses to explain how elite members of an insurgent organization decide whether to break away from the parent organization and form a splinter group. Drawing on databases about two rebel groups - the Inner Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party and the Chinese Communist Party’s Red Army in early 20th-century China, we present a hierarchy-centric theory of the rebel group’s split. We argue that an elite member’s decisions are first shaped by her position in the organizational hierarchy. The organizational hierarchy institutionalizes the distribution of power among affiliated members. This differentiation creates incentives for elites with divergent preferences to make a bid for the leadership. The hierarchy also induces status conflicts between higher-ranked leaders and subordinates. Both mechanisms lead to leadership disputes when the control of incumbents is weakened. Individual-level variations are accounted for by the outcomes of the feuds. When there are clear winners and losers, losers break off from the parent group. On the other hand, when there is a stalemate, low-ranking elites quit and create a new unit.

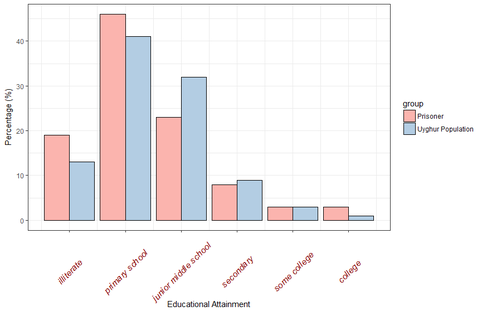

Abstract: Recent quantitative studies on Xinjiang's ethnic conflict overwhelmingly examine macro-level structural conditions that lead to the outbreak of inter-ethnic conflict in the region. In contrast, this paper explores the micro-politics of conflict in Xinjiang. Based on rarely-used primary sources, it lays out three stylized facts of Xinjiang's ethnic conflict between the 1980s and the mid-2000s. First, unlike the pattern found in other cases, Uyghur dissidents were more likely to come from lower social class. Second, with regard to contentious repertoires, Uyghur dissidents tended to use terrorist attacks as their main strategy to challenge the Chinese state. Third, Uyghur nationalist organizations were inclined to use the Islamic rhetoric to frame their collective claims. I argue that a state-centered theory, which highlights both ruling strategy and state capacity, offers a coherent explanation for the micro-level dynamics of the Han-Uyghur conflict before the mid-2000s.

1. The Political Geography of State-owned Enterprises and Conflict in Ethnically Divided Societies: Evidence from China

(with Xun Cao)

Abstract: In many ethnically divided societies, the state uses state-owned enterprise (SOE) employment as a type of cross-ethnic patronage to stabilize inter-ethnic relations. However, as increasing the allocation of SOE jobs crowds out fiscal resources that can be used to supply public goods, the state faces a trade-off between offering SOE jobs and providing public goods in curbing ethnic strife. We argue that the impact of SOE employment on ethnic conflict is conditioned upon local ethnic geography. On one hand, the ethnic composition of local communities affects how individuals assess the value of public goods. The utility of consuming a given public good is higher in regions where co-ethnics are in the local majority than its counterpart in ethnically fragmented areas. On the other hand, poverty rather than local ethnic geography influence the assessment of the utility of a SOE job. Consequently, the relative value of a given SOE employment opportunity compared to public goods is higher in ethnically diverse communities than that in more homogeneous neighborhoods, ceteris paribus. As a result, the pacifying effect of SOE employment is stronger when the level of ethnic heterogeneity increases. To test this proposition, we combine fine-grained firm-level information with county-level ethnic conflict data in China’s Xinjiang region. Using a county-year panel dataset of Xinjiang from 1997 to 2008, we find empirical support for our arguments.

Proudly powered by Weebly